Taylor Swift Buys Back her Masters - My Take

Taylor Buys her masters back - The Saga

Taylor’s letter.

https://www.taylorswift.com

My commentary on this journey, as someone who is a Taylor Swift fan, supportive of artist ownership, and a student of the music industry. All that being said, I don’t think any of this is quite as it seems in the headlines.

In 2005 Taylor Swift signed her first record deal with Big Machine Records, in Nashville. Taylor, 15 years old at the time, agreed to the a 13 year deal with the label. For the young artist, the deal would give Big Machine ownership of the master recordings. Let’s make sure we understand the pieces of pie here.

Music Ownership: Publishing vs Masters Explained

If you've followed Taylor Swift's highly publicized battle over her master recordings, you've probably heard terms like "publishing rights" and "master recordings" thrown around. But what do these actually mean, and why are they so important to artists? Understanding the difference between publishing and masters is crucial for anyone interested in the music industry, whether you're an aspiring musician, music fan, or just curious about how artists make money from their work.

The Two Types of Copyright in Music

Every song involves two separate copyrights that can be owned independently:

1 The Musical Composition (publishing)

2 The Sound Recording (the masters)

Think of it this way: if you write a song and record it, you've created two distinct pieces of intellectual property that can be owned, sold, and licensed separately.

What Are Publishing Rights?

Publishing rights relate to the underlying musical composition – the melody, lyrics, chord progressions, and overall structure of the song. This is the "song" in its purest form, before any specific recording is made.

Who Owns Publishing Rights?

Publishing rights typically belong to:

• The songwriter(s)

• Music publishers

• Both

How Publishing Makes Money

Publishing generates revenue through several streams:

Performance Royalties: Every time the song is played publicly – on radio, in restaurants, at concerts, on streaming platforms – the songwriter and publisher earn money through performance rights organizations like ASCAP, BMI, or SESAC.

Mechanical Royalties: When the song is streamed, downloaded, or pressed onto physical media, mechanical royalties are paid to the publisher and songwriter.

Synchronization Fees: When the song is used in movies, TV shows, commercials, video games, or other media, sync licenses generate fees.

Print Rights: Revenue from sheet music sales or digital notation licenses.

What Are Master Recordings?

Master recordings refer to the specific recorded version of a song – the actual audio file that was created in the studio. This includes the particular performance, arrangement, production choices, and sound engineering.

Who Owns Master Recordings?

Master ownership typically goes to:

• Record labels

• The artist

• Producers or studios - more rare

• Investors or rights holders

How Masters Make Money

Master recordings generate revenue through:

Sales and Streaming: Revenue from digital downloads, physical album sales, and streaming platforms like Spotify and Apple Music.

Licensing for Media: When the specific recording (not just the song) is used in movies, TV, commercials, or other media.

Sampling: When other artists want to use pieces of the actual recording in their own songs.

The key takeaway? Whether you're an artist negotiating your first deal or a fan trying to understand industry controversies, remember that music ownership is more nuanced than it appears. Every song lives as both a composition and a recording, and whoever controls these different aspects holds different pieces of power in the music ecosystem.

As an artist grows larger, it’s typical to see them take on a record deal, and a publishing deal if they’re a singer-songwriter. For Taylor she had both, the record deal with Big Machine, and publishing with Sony Music Publishing. The record deal at the time was pretty standard for a teenage artist like Taylor. Without much leverage, a deal that would pass ownership of master recordings to the label is not rare. To take a chance on a young artist, and offer major investment to them, has to require an exchange of value. During this stretch of 13 years, Taylor would release 6 albums and two live albums under Big Machine, “Fearless, Speak Now, Red, 1989, and Reputation.”

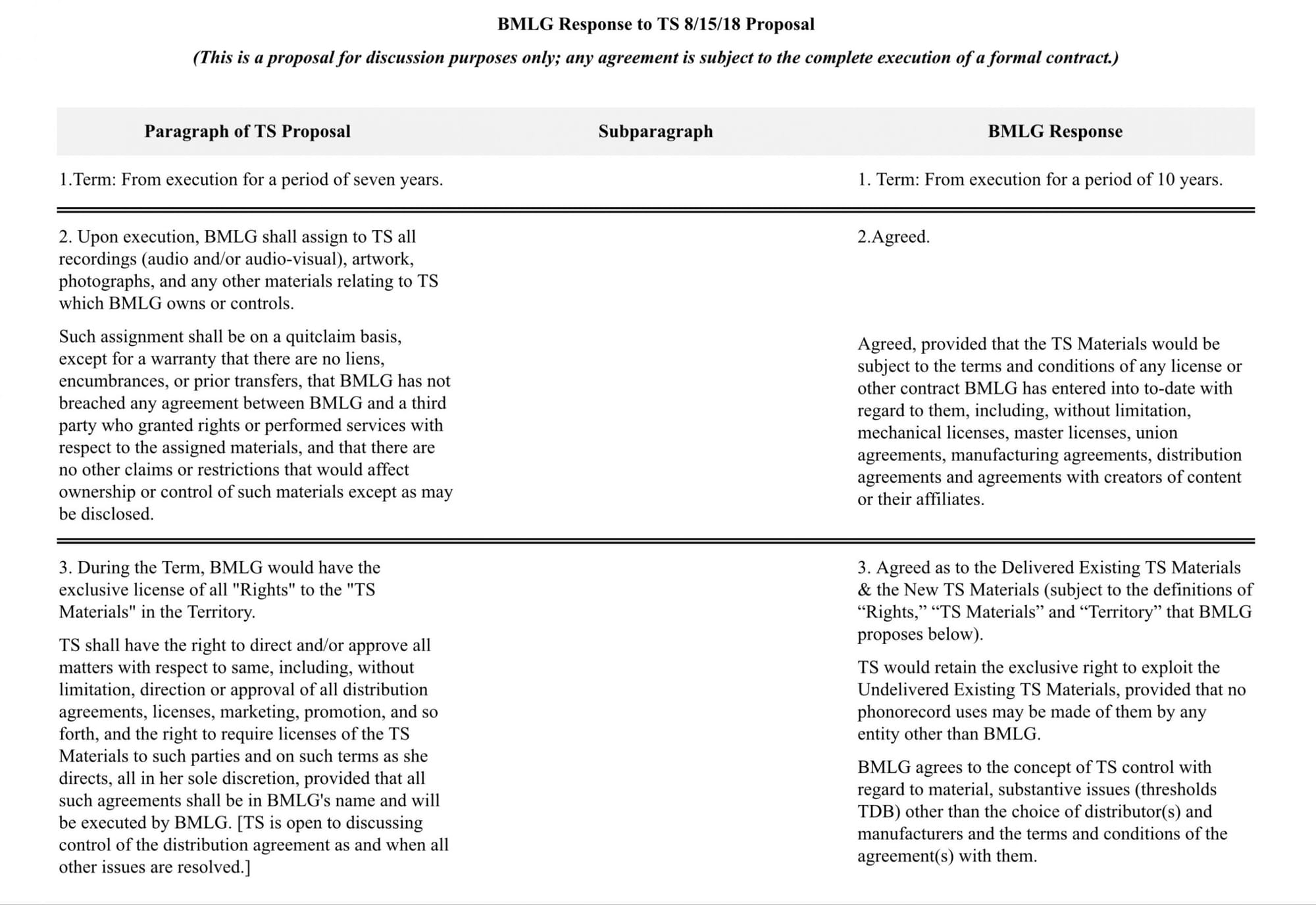

At the completion of her term with Big Machine records in 2018, negotiations between Swift and BM would begin again. Now Swift, one of the globe’s biggest artists, was now in whole new territory. See below, the offering from BM.

Scooter Braun enters the equation.

I am not interested in getting into the drama between Braun and Swift. There are plenty of places to read about their personal grievances and the rough situation that surround Taylor, Kim K, and Kanye West. I am more interested in discussing the business. Braun’s leverage comes from a management roster headlined by A listers like a young Justin Bieber, Ariana Grande, and Kanye West. Eventually Braun grouped his subsidiaries into Ithaca Holdings. It was this group backed by Carlyle that bought Big Machine Music group in 2019 for 300 million dollars, which included Swift’s Masters. This is the point when Taylor gets pissed. Because now a main figure in this feud that deeply affected her well-being, now owns her masters.

All this is really what sets up the unprecedented rerecording campaign that would begin. Artist’s have rerecorded songs before to create separation between themselves and a past deal. Prince and Frank Sinatra are generational artists like Swift who rerecorded songs during disputes with their labels. But to be in Swift’s cultural moment where the rerecording can actually outperform the originals and re-influence the whole catalog is certainly unprecedented at this scale. One thing Taylor has done really well as a marketer is finding ways to still “ intimately” engage with her fan base despite the mass of fans globally. To have her rerecorded albums include the “from the vault” tracks to offer new content was key in my opinion. It transforms from a nostalgic reprise of old songs to an evolution and maturity of the original record for fans to grasp on to. The way “All to Well” returned to the front of the present moment with the 10 minute version was genius. When you think about what is going to engage fans and create frenzy, no one does it better. Even without the relevance of Taylor’s feud with Braun, and fans having her back, I still think the presentation of these rerecorded albums maintain a lot of additional value.

With a case like this, I always like to consider its relationship with everything else going on in the entertainment business. Because its sort of on an island as far as impact within music, it was about time historically for this to happen. Musicals to me are a great example of audiences enjoying evolutions of existing art. Take, West Side Story for example. On its own a reimagined version of Romeo and Juliet, spun into the Upper West Side of the 1950s. First appearing on Broadway in 1957, it was brought back with revised versions in 1964, 1980, 2009, and 2020. With the original movie coming out in 1961, and recently a new version in 2021, 50 years later. All the same story of the Jets and Sharks and the tragic love story between Tony and Maria. Now each of these productions featured new cast and new producers on stages around the world. You went into the theater excited to see how new faces could reimagine a classic story. For Taylor’s albums it’s obviously still her performing her songs. But really, the sentiment was different. I believe fans felt like it was a different more mature version of the same Taylor who originally recorded these albums, re-exploring them within new context. With fresh production, and fresh performances, it feels like a revival of the same record, just dressed in a slightly new way.

Taylor just bought back her masters. The fact that she made this deal happen speaks to not only the dedication she has had to her pursuit of ownership, as well as the massive amounts of capital she’s been able to produce through her catalog and global tours. Shamrock capital, which was the current owner of the Masters sold them back to Taylor for the price they were bought, 360 million. Shamrock’s announcement of the news was simple, “We are thrilled with this outcome and are so happy for Taylor.”

The last thing worth exploring that is rather complicated is the way that Taylor Swifts catalog evaluation would have evolved overtime. Not only because of her superstardom but also because of the rerecords. Taylor buys back her albums for a rumored 360 million, around the equivalent cost they were bought for by Shamrock Capital. However before the rerecording started it might’ve been reasonable to value her master’s closer to 450 or 500 million dollars. Probably around later 2020 and into 2021 when the rerecording started would’ve been when the catalog was worth the most if you factor in a traditional 15x EBITDA multiple. However, once the rerecording release, the revenue of the original albums of course went down substantially, dropping the value of these original albums. So did Taylor get a good deal? Well, yeah. She ultimately paid below peak value, and retains her life’s work. Although, she did buy a depreciating asset but that is by her own doing. Based on her extreme streaming revenues, this purchase will repay itself and work into the positives within 5 years. The financials however, did not ever seem like Taylor’s ultimate goal. Braun on the other hand in the course of about two years would’ve made about 250 million off Swifts catalog through the purchase of Big Machine and then the sale to Shamrock Capital. So in the end, both of these parties win in their own ways. Like it or not, you have to tip your business cap to both of them.

As this saga ends for now I think I find myself drawing a few conclusions:

- This is a celebration of what Taylor did without her masters in the pursuit of buying them back.

- I don’t think Big Machine Records deserved to take any heat. None of the business they did was unethical or malicious compared to standard industry practice.

- Scooter Braun is an example of the fine line management must walk between supporting your roster and still maintaining positive public image and public relations.

- What can this teach us about what makes a successful revival? Why is it such a popular strategy in today’s greater entertainment business, and when do fans actually become excited for them?